The House of Windows

Isabel Ecclestone Mackay

London: Cassell, 1912

Writing on Ontario, opium and cocaine in Isabel Ecclestone Mackay's 1917 Up the Hill and Over, I reported that the novel featured "perhaps the most remarkable and improbable coincidence in all of Canadian literature."

The House of Windows challenges in an entirely different way. Here the reader must believe that all characters remain blind to coincidence, conduction and consonance, and are each incapable of concomitance.

Mrs Mackay's story begins in the ribbon department of Angus and Sons, a fictitious department story in a fictitious city that appears to have been modelled upon Toronto. It's the day of the semi-annual sale,

with frenzied women causing chaos through collapsing displays. "SACRIFICE OF ALL RIBBONS WITHOUT RESERVE," the adverts announce, "EVERYTHING SLAUGHTERED!" At the end of it all, the shop-girls – known as "Stores" – wade through paper from the unwound bolts to find an abandoned go-cart with baby girl within. There's some talk of calling the police, but the newest Store, Celia Brown, comes forward to care for the child as she would a sister.

Not one of the shop-girls, good-hearted Celia included, gives so much as fleeting consideration of the news dominating the city's dailies. Baby Elice, daughter of wealthy Adam Torrence and wife, has been kidnapped. This tragedy will soon lead to the premature death of poor Mrs Torrence. Devastated widower Adam, bereft of wife and child, will take young Mark Wareham, a not so distant relative, to be his ward.

As Christine Brown, the abandoned baby is raised by Celia and her blind sister Ada. She grows to become a beautiful young woman, while spinster Celia loses looks and energy. Angus and Sons is to blame for the latter's decline. The work of a Store – ten hours a day, six days a week – is hard. Everyone knows that the stools behind the counters are just for show.

You musn't blame Celia's employer – who, as it turns out, is Adam Torrence. This man of wealth pays little attention to the store, and even less to the Stores, because the money they bring flows so steadily. Thoughts that stray in the direction of Angus and Sons invariably concern propriety. Adam is firm that all shop-girls hired have additional sources of income lest they turn to... become... find themselves... Oh, he cannot bring himself to express his fears.

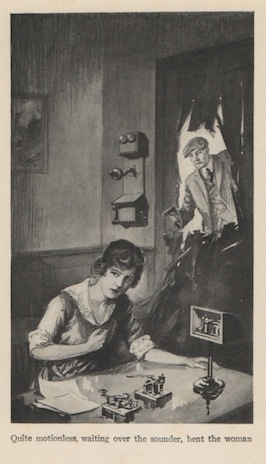

Crisis comes to the cramped Brown flat when Celia suffers a nervous breakdown. It's unfortunate, of course, but her timing is good in that Christine has secretly been job hunting. During her search she meets Adam's unofficially adopted son Mark. The moment, which takes place when he pushes a man to the ground for daring to talk to her, is captured in illustrator Dudley Tennant's frontispiece.

Mark falls for Christine in such a way that the throb escapes no one. Disapproving his dalliance with someone named "Brown", someone who is plainly of the lowest class, the Torrence family – Adam and elder sister Miriam – dispatch Mark to Vancouver.

Adam is next to happen upon Christine. For a moment he gives consideration that this Miss Brown might be the same young woman in whom Mark is interested – but then Brown is such a very common name of very common people. That said, Adam is distracted, bothered and fairly won over by Christine. She is very much a lady, despite her lowly family. The mere description of her hair – "honey blonde" – brings to mind that of his dear late wife. And, oh, doesn't Christine have the same eyes, laugh and smile of his dear departed sister.

Sixteen years into the story, everyone meets everyone else, which I suppose can be put down to coincidence. It's at this point that another plot, a nefarious plot, is revealed. We learn that Christine (née Elice) had been kidnapped all those years ago by an old crone who believed her daughter was ruined in working at Angus and Son. The poor Store turned to... became... found herself... Oh, I cannot say.

Weirdly, improbably, the crone thought that by leaving Elice in the ribbon department the girl would grow up to work in the store. Weirdly, improbably, she was right.

Christine – Elice, if you prefer – is kidnapped a second time. More coincidences ensue. I recognized them all.

Query: How is it that the Stores made no connection between kidnapped Baby Elice and the infant that had left in the ribbon department? Celia explains it all:

"We read it in the papers. But we did not feel especially interested. We did not know who Mr. Torrence was. He was just a name. We did not know he had any connect with the Stores. And this baby – so evidently a neglected and unwanted child! – it would have been a miracle if the coincidence had struck us."

Object and Access: My copy, inscribed by the author, was purchased just last month for US$25 from an Illinois bookseller; I'm thinking it's a first edition. While there are four copies currently listed online, each from sellers who claim the same, at least two lack the elegant monogram pictured above. I suggest that these are at best second state. Either way, expect to pay between US$50 and US$100.

Being in the public domain, print on demand vultures are all over this one. Nabu, General, Pranava and Repressed bring their usual ugliness, but the worst comes from the confusingly-named Book on Demand of Miami, Florida:

This book, "The house of windows" [sic], by Isabel Ecclestone 1875-1928 Mackay [sic], is a replication. It has been restored by human beings, page by page, so that you may enjoy it in a form as close to the original as possible. This item is printed on demand. Thank you for supporting classic literature.

You're welcome. Now, if you could just put some human beings to work on that cover.

Nearly all our universities have copies, as do the public libraries of Toronto and Vancouver. Library and Archives fails yet again – given current policy, one wonders whether it will ever procure a copy.

+.png)